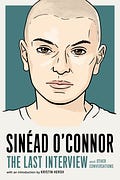

Review: Sinead O'Connor, The Last Interview

Review: Sinead O’Connor, The Last Interview

Melville House, October 29, 2024

After the death of a cultural figure, Melville House will sometimes select interviews that the person did over the course of their career and publish them. This collection of Sinéad O’Connor’s interviews, including an interview she did on The View in 2021 before her death in 2023, is the latest in the series.

Like many people in the Gen X cohort, I encountered Sinéad O’Connor when I was a teenager and she was an emerging pop star. I first remember the video for “Mandinka,” where I heard her incredible ability to reach for a whispery high note then dive for a growling low note. Sometimes the change was crisp and clean; sometimes there was a hitch that reminded me of the “lonesome holler” in American bluegrass music. I took her completely at face value: shaved head, black boots, unapologetic stance with a mirrored guitar blinding the camera. I did not find this off-putting or needlessly defiant. I thought she was someone who knew herself in the way that I wished, as a teenager, that I knew myself. I knew nothing else at all about her.

This is where The Last Interview begins, these early years, and it stretches across O’Connor’s career through her retirement around the turn of the millennium and into her second stretch of making music and writing a memoir in the twenty-first century. The interviews throw a certain light on how O’Connor thinks and speaks, but the collection really shines a Klieg light on music and pop culture journalism, and its relation to a controversial star, over the course of more than thirty years.

Take, for example, Sinéad’s famously shaved head. She offers stories of its beginning at nearly every stage of her career, and the stories say as much about her self perception as about how she is perceived by media and culture. In the first interview, conducted by Kate Holmquist for The Irish Times in 1986 when O’Connor was nineteen, she says:

I have a skinhead, but I’m not a skinhead. I have the haircut because it makes me feel clear; it makes me feel good.

The next interview, by Barry Egan for NME in 1988, is the absolute worst of music journalism—overblown and more taken with itself than the subject of the interview. She’s much pricklier here, and she only mentions her hair when asked what she looks like: “Shaved head. Small. Thin. Not very thin though. I’ve got really, real horrible legs and a big nose.”

David Wild’s Rolling Stone interview comes after the success of I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got in 1993, an album that I can sing every word to still, if you ask. Wild seems genuinely interested in her thought processes during the course of this conversation. And yet he brings a tangent back on track by saying, “Let’s talk hair.” And O’Connor does, but her story at this point in her career shines the light from a different angle, one with a current of defiant agency:

Years ago, Chris Hill and Nigel Grainge [the heads of Ensign Records, O’Connor’s label] wanted me to wear high-heel boots and tight jeans and grow my hair And I decided that they were so pathetic that I shaved my head so there shouldn’t be any further discussion. I also did it for other reasons, but that told them.

This is a reaction to being told what to do and how to present herself rather than, as she said in 1986, making her “feel clear.” She’s also straightforward with Wild about the fact that she doesn’t find herself attractive or consider herself a sex symbol or role model no matter what her hair looks like or how she dresses.

Spin also did an interview around this time, conducted by the publisher himself, Bob Guccione, Jr. He considers her a powerful, talented genius, and his conversation with her goes very deep very quickly. She answers his short questions on spirituality and religion, child abuse, war, racism, the state of music, feminism pro and con, often at length. Eventually does ask if she’d grow her hair out if a man she loved asked her to, and she says no. (He’s skeptical throughout of her ability to feel complete without a man.) He asks if this “intimidation bit” is something she’s created, and she says “Absolutely,” though it’s “not a conscious creation” on her part.

SPIN: Isn’t that why you cut your hair?

O’Connor: No. I just refuse to allow it to make me become something else.

The conversation starts to veer away from the topic and toward the things she has to deal with as a public figure, but Guccione steers it back. He wonders if she shaved her head because she was a victim. Same story, new light:

First of all, shaving my head to me was never a conscious thing. I was never making a statement. I just was bored one day and I wanted to shave my head, and that was literally all there was to it. I already had it shaved on the sides and it was about as far as I could go. I think fiddling with the hair is a huge subconscious statement, yeah. Yeah, I suppose it Is a subconscious rejection of conformity and of the family and everything that the word “family” can mean. I’m growing it now.

This version of the story seems to swing back toward feeling clear. It doesn’t mention the label guys. In the Rolling Stone interview, she leaves room for “other reasons” besides telling men in power to fuck off. The boredom and an indifference to conformity she expresses in the Spin interview are enough “other reasons” for most people to shave off the rest of an undercut.

As she ages, her hair becomes less of a subject of fascination. For one thing, she steps out of the spotlight to raise her children, which she discusses for the Irish Independent. When she’s interviewed in 2005 about her album of Rastafarian songs for Inside Entertainment, she is asked late in the conversation if she would grow dreads; she would not. During a radio interview in 2007, her hair is only mentioned in passing. In a long discussion ranging from faith to her recording process, Jody Denberg notes that the media “liked to talk about your hair or your sexuality or other tabloid stuff,” and no more is said about it.

The zeitgeist (and the range of hairstyles considered acceptable across genders) had changed by the 2010s. For a 2014 interview in Pride magazine, Chris Azzopardi asks about her shaved head as a “symbol of identity and empowerment.” O’Connor’s brief answer encompasses the self-determination of her early stories, the rebellious reaction of her pop star era, and the acceptance that can come with time:

I’m quite pleased that I look the way I look, and I guess I associated the hairdo with me. I don’t feel like me if I don’t have my head shaved. And yeah, it does mean, too, I can put on a dress and I’m still not selling what everyone else wants me to sell.

In the last interview in The Last Interview, O’Connor comes back around in 2021 to including the record executives in the narrative. But she also wants us to see the story the way she does in her fifties, as “quite funny” rather than as enraging. She tells the hosts of The View that the label asked her to grow out her “bit of a mohican” and dress sexier, which she didn’t want to do. She told her manager about it, and “he said, ‘Oh I think you should just shave your head.’” So she marched across the road in London and had a Greek barber shave her hair off, despite his trying to talk her out of it. It’s told as a laugh, as a youthful fuck you, by a middle-aged woman who has spent her life saying fuck you with varying degrees of intensity to anyone who tried to control her.

She makes very clear in these interviews—which are about far more than her hair—that she wanted the money, she was happy to win the awards, and she was genuinely grateful for her fans. She also wanted to present herself on her own terms, to bring her politics to the pop arena, to fight injustice, and to maintain a sense of integrity. She got shit on for that for a long time, but in the end, Sinéad was right.

Sinéad was right.

Sinéad was right.

You can buy all of KHG’s books and those she recommends at Bookshop.org. You can also buy her books in paperback and ebook formats directly from Practical Fox.